Q&A with Michele Landel

Your embroidered bed linens explore themes like memory, power, and identity—how did you begin using domestic textiles as a canvas, and what draws you to their intimate, everyday nature?

I began using domestic textiles as a canvas when I started brewing natural dyes in my kitchen and dyeing small scraps of fabric—cloth baby diapers, antique tablecloths, stained tea towels—which I then stitched onto paper. At the time, I was exploring the physicality of gender roles through these small, intimate artworks. (see my For There She Was series)

As my themes evolved and my work became larger, I began working exclusively with bed linens. I’m drawn to their associations with domesticity and active intimacy. A bedsheet is an object used daily to provide warmth and protection. It is a deeply intimate textile where life begins and ends, and where we go to rest, heal, and make love. On these linens, my photographs become sensual and soulful. The material is meant to activate tactile memory.

Your technique blends burned, quilted, machine‑embroidered photographs and paper to create layered, fragile imagery. Could you walk us through your technical process—from photographic manipulation to final textile collage—and any innovations you've discovered along the way?

The photograph is the most difficult part, and it always takes me the longest. It forms the foundation for everything that follows, so getting it right is essential. I spend a lot of time composing and adjusting until the image captures the mood and emotion I want to convey.

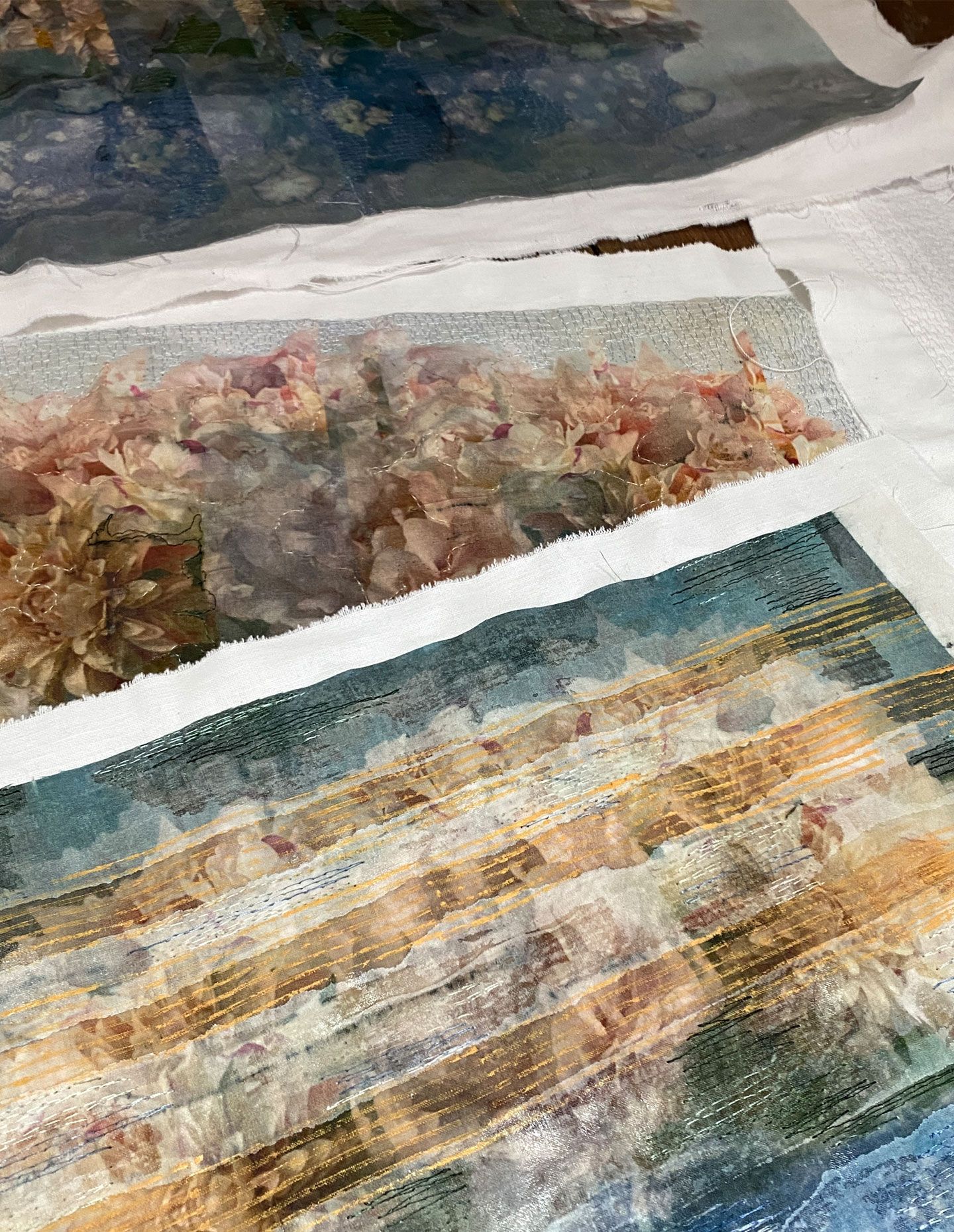

I then print my photographs directly onto bed linens, cutting them into small pieces to fit through the printer. It’s a finicky and time-consuming process, but the specific texture of the fabric is important to me, so I print it myself. In the last year or so, I’ve begun painting the images with wax to bind the ink to the fibers. This creates a watercolor-like effect while ensuring the image’s permanence. Depending on the size of the artwork, a single image can be composed of over thirty smaller pieces of fabric. I piece the image together like a patchwork quilt, then machine embroider the individual fragments into a single image. I use stitch patterns that reference mending and quilting but also evoke more abstract ideas such as time and movement.

Your work combines photography, embroidery, and reclaimed textiles—how do you decide which medium takes the lead in a given piece, or is it always a balance?

The photograph always comes first, the textile second, and the embroidery third. I make the photograph, I find the textile, and I stitch the image together. There is a natural balance in the final pieces.

You mention reconstructing domestic interiors into “fragile, fractured memories”—what role does memory or personal history play in the creation of your work?

At a certain level, all artwork is autobiographical. Lately, I’ve been working with flowers that I grow and cut from my garden. My oldest child is leaving for university this fall, and for the last year or so, I’ve been thinking a lot about the fleeting and precious nature of family life. I cut and photographed bouquets of spring flowers. As time passes, the flowers wilt and fade. By repeating the photographic exposure, the bouquets begin to vibrate and echo, holding both their presence and their disappearance.

When I print these images, they are divided across many pieces of fabric. The edges never align perfectly, and the fabric stretches and distorts the image further. For me, these works become like memories themselves—beautiful and precious, yet fragmented, shifting, and never remembered in exactly the same way.

In a time of digital saturation and instant imagery, how do you see the act of hand-stitching as a form of resistance or commentary?

Machine embroidery traces thin, irregular lines—part scar, part map—across the surface. Flowers collapse. Shadows multiply. Objects shift and vibrate. What once felt familiar becomes unstable. In a culture saturated with manipulated images and curated illusions, I lean into rupture. Walter Benjamin warned of the aura lost through endless reproduction; I stitch it back in, drawing on the intimacy of embroidery and mending—through labor, slowness, and touch.

These are not pristine images. They are disrupted, broken, stitched-over inner landscapes. I reclaim the handmade as a challenge to the polished, the fast, and the fake.

For me, collecting and supporting textile art is also a political act and form of resistance. It reflects a belief in the value of materials and methods that have historically been overlooked or dismissed. When someone invests in textile work, they are not only appreciating its visual beauty, they are also acknowledging the cultural and emotional labor behind it.

In that sense, the collector becomes part of the work’s message. They are helping to elevate the history of women’s work and bring the often private, domestic world of textiles into public and artistic spaces. That act of recognition and support carries real meaning.

Images courtesy of Michele Landel